By David Montieth

Former Mountaineering Scotland Mountain Safety Director David ‘Monty’ Montieth tells a cautionary tale about getting caught in an avalanche. There are lessons to be learned – including that it CAN happen to you.

The 7th January 2003 dawned cold and crisp in the Cairngorms. The plan was to take my eldest son Alasdair on his first winter route in Coire an t-Sneachda, in the Northern Cairngorms. We had already climbed a lot together in summer, and had spent many days in the winter mountains developing axe and crampons skills and looking at the special demands of navigating. My choice for Alasdair’s introduction to winter climbing was the classic Grade 1, Jacob’s Ladder.

There had been the usual early season promise with a heavy snowfall at the end of October. In fact my log book records an ascent of The Messenger on the Mess of Potage on 26 October 2002. However the early snow had soon gone or been transformed to nevé in the nooks and crannies of the corries. Fresh snow fell on this old base in early January 2003, an extensive covering, which gave us a fairly strenuous walk into Sneachda that morning as the keen south-easterly wind filled in the previous day’s tracks. The forecast avalanche hazard was moderate and we trudged up the approach path anticipating a good day.

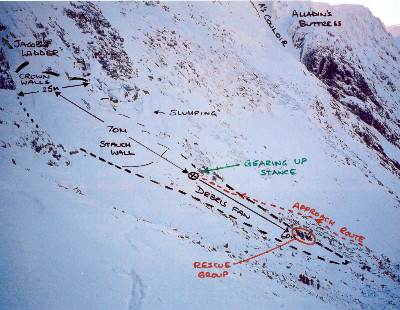

An alarm bell rang in my head when we met two climbers walking out – too much fresh snow and spindrift was their verdict. The wind was definitely stronger than anticipated but their view was countered by another early riser exiting the corrie who had soloed Aladdin’s Mirror Direct and seen two skiers descend the Couloir. Things can’t be that bad then! We continued apace, following a deepening trench through the soft snow as we closed with the cliff. Up ahead several climbers were approaching the base of Jacob’s so I slowed down to see where they might go; they split and prepared to go left onto the Mess of Potage. We reached a platform prepared by the previous day’s teams and prepared to gear up.

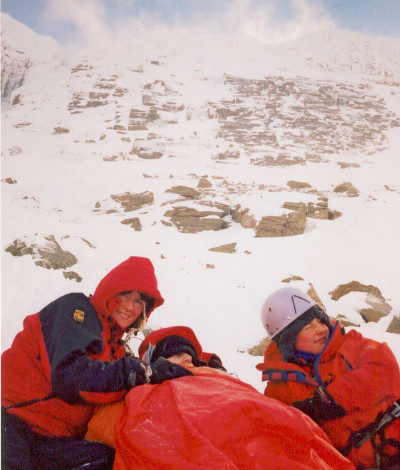

In the eerie half-light of an orthopaedic ward in the wee small hours you have a lot of time to think things through. Embedded freeze frame memories flashed through my mind: the crump as the avalanche released; the focused image of tons of snow breaking into slab above us; my cry, “run right”, as I tried to steer us out of its path; the seemingly gentle push as the snow reached us, rapidly turning into a chaotic, tumbling motion; the blood on the snow when we finally stopped; the friendly banter with our rescuers as we waited for the Sea King to ferry stretchers to the rescue site; the hypnotic slow motion of the spiralling stretcher and the raw power of the Sea King’s rotor above as I was winched up. All of this impregnated with huge relief that we had survived albeit with bruises, breaks and scrapes. I had not been the agent of my son’s death.

We later gained a detailed insight into what had happened. Basically we were caught by a pocket of windslab over soft snow on the apron just below the entrance to Jacob’s ladder. When it released it swept the accumulated soft snow down onto us. We were gearing up on the edge of what became the debris fan and just missed getting out of its path. Unfortunately it took us onto rocks below, hence the scrapes and bumps. But we had not been buried!

Our luck held in the form of a Glenmore Lodge party, the group we had seen on the Mess of Pottage. Within minutes one of the Lodge staff was on the radio back to Glenmore. A helicopter was scrambled from RAF Lossiemouth after only 15 minutes. Two SAIS forecasters were up on Windy Col assessing the snow and they also came down on skis to assist.

The SAIS team later passed on the snow profile for the day, which clearly shows a very weak layer at 20cms, the new snow above and soft snow beneath on the old snow base – the snow that had fallen the previous October. By January this base had been altered through freezing conditions producing a very hard base with buried surface hoar on top. There was a temperature unconformity at about 12 cms reflecting the windblown snow being brought in on a cold SE wind. Despite the avalanche hazard being moderate the build-up of windslab on the scarp slope on top of the new snow was significant.

Two weeks later during a pre-arranged visit to the Aeronautical Rescue Co-ordination Centre at RAF Kinloss we were able to view the archived plot of the rescue. It took less than two hours from avalanche to Rescue 137 landing on at Raigmore prior to us being admitted to A & E. We also visited the SAIS office to discuss the event and later met with them and some of our rescuers in the Bridge Inn to say thank you. The conclusion was that the wind had subtly changed overnight, loading the particular aspect by Jacob’s Ladder. But there was no obvious cause to the release, it was just spontaneous.

Within a week my son Alasdair was running in his school cross country race. I was back on the hill in mid-March after eight weeks recovering from a cracked hip and twelve stitches in my head. It was a salutary lesson that despite checking weather forecasts and avalanche information and being aware on the approach you can still get caught out. This time we had been lucky.