This is one of a series of misadventures in Scotland's mountains - either close calls, accidents or mountain rescues - where the protagonists look back and identify mistakes they made which could have avoided the trouble. These tales are generally anonymised and are not so that people can point fingers, but so that they can learn from others' mistakes and avoid having to make them for themselves.

My partner and I were on day three of a two-night/three-day expedition from Aviemore down the Lairig Ghru and back up Glen Derry with overnight camping at Corrour and Fords of Avon. It was October and a typical autumnal Scottish walk with variable cloud, reasonably strong wind and showers, but winter was yet to fully set in. At the time we were reasonably experienced summer hillwalkers but didnít fancy being on the Cairn Gorm plateau in poor weather so had deliberately planned the route to stay at lower level.

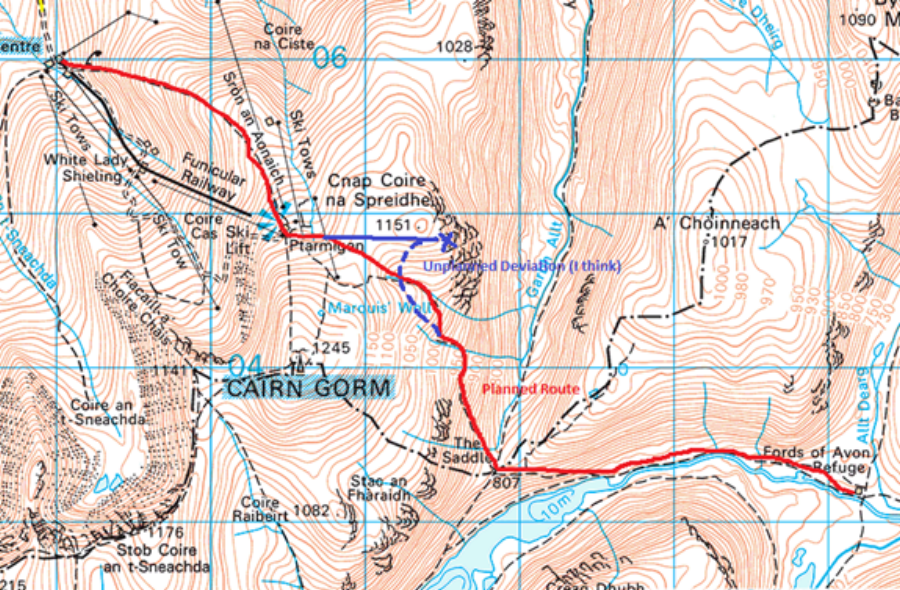

On day three we hoped to do the one bit of higher level walking crossing from Loch Avon over to the Ski Centre, to hopefully have a hot lunch at the cafe to celebrate being on the last leg of the trip.

As we ascended visibility became gradually poorer, but so gradually we barely noticed that we had lost any reference point, and upon reaching the top of the slope we began descending what we thought was the NW aspect, expecting to come across a ski tow any minute. I was surprised then when we came across an unexpected cliff top with no sign of the ski centre and experienced the sense of developing panic of being lost.

It would have been easy to continue walking off in another direction, but it was drizzling in the cloud so my eminently sensible partner suggested to pausing to put on an extra layer and have some chocolate before starting to problem solve and this definitely saved us time in the longer run.

We were able to reorientate roughly based on the aspect of the cliff and how long we had been in cloud. However this suggested that we had been walking 180 degrees from where I thought. Initially I even thought that the compass might be broken Ė which seems like a ridiculous thought, but shows how strong the sense of disorientation was, and was not helped by having left the compass at the bottom of the rucksack for most of our walks. I was worried that we might have unwittingly walked into hostile terrain and how would we get out.

The lifesaver in this case was the offline mapping and GPS on my phone which confirmed that the compass was correct and we were indeed roughly where I thought we were, which fortunately allowed us to walk an easy course west until we came across a ski tow.

Although we got ourselves out it was a real wakeup call to how quickly you can become disorientated in creeping low cloud. It showed how strong the sense of disorientation can be: so much as to almost cause you to disregard your navigation tools. It also showed that between us we had the ability to reorientate ourselves and navigate back on course Ė but that we should have been much more proactive with navigation before the weather got really bad.

It prompted us to go on a winter skills course at Glenmore Lodge and this together with the experience as a whole taught us a number of things:

1. Be proactive with navigation skills. At the time we were fair weather walkers and whilst we were carrying maps and compass, we considered them as emergency equipment rather than for regular use and it had been some time (if ever) that I had used them in anger. The winter skills course taught us to make a point of having the compass out, taking a bearing or practice reorientating on most walks even if the weather is good, giving confidence in the kit and skills for when it is really needed.

2. Similarly, have the compass to hand at the first sign of weather coming down. We could have probably avoided this whole issue if I hadnít waited until realising we were off course to try and reorientate. Likewise pay attention to the level of visibility Ė looking back on the photos from that day I am amazed that I didnít recognise the developing difficulty sooner.

3. When lost, stop and think. There was a startling sense of panic which came over when coming across the top of a cliff we were not expecting. Having something to eat and putting on an extra layer before starting to problem solve made the situation much more manageable.

4. Offline mapping software and GPS bailed us out and gave us the confidence to rely on our compass skills. There are obvious limitations to this technology but itís definitely good to have available as a get out of jail option.

5. Get a personal locator beacon. This made us think what would have happened if we had needed help to get out and so we decided to invest in a PLB as a last line of redundancy in an emergency.

6. Go on a course. Soon after this we arranged to go on a winter skills course, which was excellent at consolidating skills and developing confidence for those bad weather days at either end of the season.

Navigation isn't a dark art. The basics are simple and the more you practice the better you get.